Understanding Global Exchange: A Route through Artefacts

Linking economic systems through museum exhibitions at the V&A, Burrell Collection, Gulbenkian Collection and British Museum

Safya Morshed

8/1/20254 min read

As part of our research goals of identifying how global exchange influenced and impacted institutions and trading cultures in the early modern world, the INTRECCI team has been visiting museums and special exhibitions to identify the kinds of objects which were traded across Eurasia and Africa. In doing so, we attempt to better understand the routes and methods that early modern traders used to transport and acquire the manufactured objects, but also the manufacturing techniques and diaspora networks that were employed in developing global trade. In doing so, the project captures a better understanding of how widely globalisation influenced artwork and manufacturing designs within the early modern Indian Ocean world, as well as an understanding of the kinds of institutions that were used to organise the trade.

So far, team members have collectively and individually visited a number of different UK based and international exhibitions, including: The Great Mughals: Art Architecture and Opulence exhibition at the V&A museum in London, the World Museum in Liverpool, The Burrell Collection in Glasgow, the Gulbenkian Collection in Lisbon, the Museu Nacional De Arte Antiga in Lisbon and the Silk Roads exhibition at the British Museum in London. Through this process, the team has identified a series of fascinating objects which highlight the breadth and complexity of the trade between distant regions. The nature and design of the objects provide an indication of degree of market competition within Eurasia across long distances, where local producers competed and collaborated with contemporaries who could live on the other side of the continent. This blog post will highlight a few of the artefacts which provide a deeper understanding of how globalisation affected patterns of exchange in the early modern world. In doing so, it will note three broader takeaways from the objects seen so far.

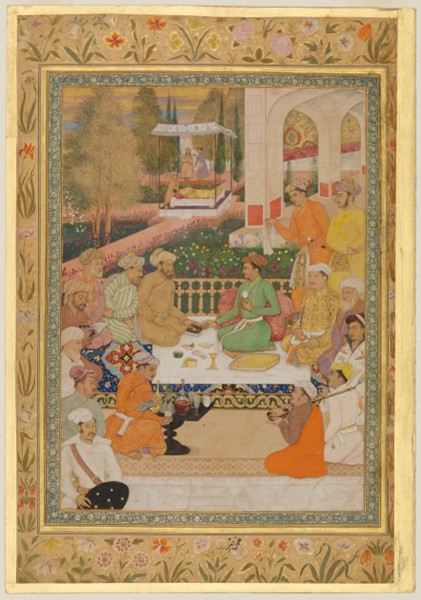

The first broader takeaway is how artwork and design in the Persianate world was influenced by the global trade of the era, especially with regards to how Mughal elites developed a taste for international luxury items. In a similar way in which scholars have argued there was a strong demand for Chinese porcelain and Indian cotton amongst European elites, elites in the Mughal empire coveted and collected artwork from all over the world. Some of these items were brought by European travellers as gifts for the Mughal rulers and elites – for example, Figure 1 shows a Mughal miniature from the Padshanama which depicts European traders bringing gifts to the Mughal emperor which the V&A Mughal Art exhibition has speculated included Japanese lacquered wooden boxes and emeralds from Columbian mines.

However, European traders were not the only route through which objects entered the Mughal domain. Mughal royalty and elites had a strong appreciation for Chinese porcelain, much of which was received through trade with Safavid Iran. Like the rooms dedicated to Chinoiserie in European palaces like the Schloss Schonbrun, Mughal architecture like the Tomb of I’tamid ud Daula and the Chini ka Rauza (literally Mausoleum of China) could often incorporate niches in the walls designed to hold imported Chinese porcelain known as Chini Khana, a fact which is indicated by the paintings of vases incorporated into those niches. Mughal Miniatures, which often reflected contemporary events, reveal how imported objects were used in court life. For example, in figure 1 below shows an image of Mughal princes using porcelain cups from China, a Venetian decanter, Iranian flask, and a gentleman to the right wearing a white clothes imported from China with bird prints on it, all of which are real objects that the team of curators of the V&A exhibition Mughal Art exhibition identified through the painting’s accuracy of their depiction.

The artefacts also indicate that demand for foreign designs and attempts to sell in foreign markets could quite strongly influenced the types of designs that artists in the Persianate world adopted. For instance, seventeenth century intricate wooden cabinets manufactured in Gujarat could often include images of European men or depictions of angels which were clearly designed to appeal to the European trade. At times, manufacturers copied foreign designs in their creations knowing they had broad appeal among consumers. Figure 2 depicts a porcelain dish manufactured in 16th -17th c. Safavid Iran from the Burrell collection which clearly copies a Ming Porcelain design. Similar artefacts exist in the Gulbenkian museum, which highlight how early modern Turkish porcelain was influenced by Chinese designs in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Figure 2: A dish made in 17th century Iran (Safavid empire) which imitates Ming Chinese porcelain designs. Source: Image taken from The Burrell Collection, Glasgow

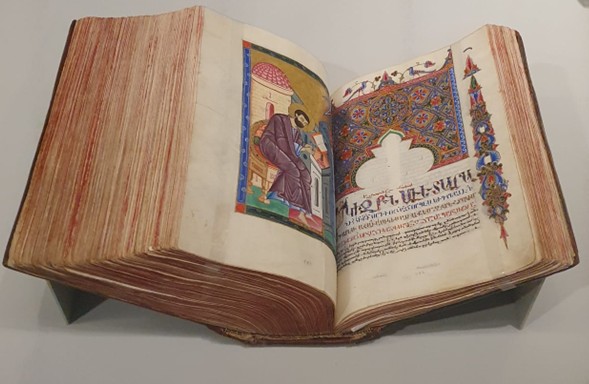

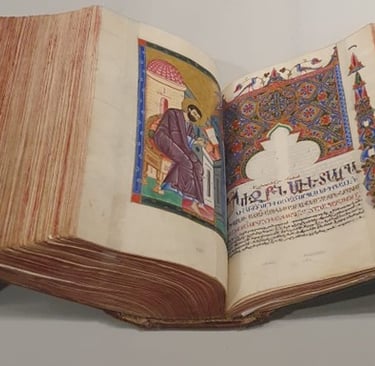

The objects often highlight the role of trading companies and diaspora networks in developing the trade and allowing it to promulgate across very long distances. Through the inland routes, several objects indicate that the Armenian diaspora played a key role in trade. Figure 3 depicts a bible which in 1623 an Armenian merchant, Khodja Nazar, who lived in Isfahan had commission from Constantinople which was 1800 kilometres away. Armenian merchants also formed close networks within Mughal circles, which allowed them to manufacture and export a variety of items like Brass ewers across the Islamic world. The trading institutions adopted by diaspora networks likely contrasted with the state-sponsored European trading companies which perhaps were less integrated into the internal Persianate merchant networks. With regards to internal Asian trade, European companies perhaps were more reliant on what was proximate their colony outposts like Surat, though also perhaps their shipping technology allowed them to reach very different markets than diaspora communities would use.

Figure 3: Bible commissioned from Constantinople (Ottoman empire) by an Armenian merchant living in Isfahan (Safavid empire) in 1623. Source: Picture taken from The Gulbenkian Collection, Lisbon

Artefacts from the sixteenth and seventeenth century Persianate world demonstrate the complexity of trade patterns and institutions which were developed in the early modern Indian ocean world. In a region where markets were predominantly free, international trade thrived, and global actors from across the world came to the region to engage in a promising exchange. The objects highlight the fascinating layers of actors and institutions that collided and traded on the continent, a factor that made the region a playground for international conflict as well as institutional and economic dynamism in the early modern world.