Blowing Smoke

The Art of Diplomacy at the Mughal Court

Shounak Ghosh

8/29/20256 min read

The coming of tobacco to the Mughal court is a fairly well-known episode in South Asian history and took place during a period of quickly growing commercial and diplomatic interactions between the Mughal empire and the wider world. The story goes that, in 1604, the Mughal emperor Akbar’s envoy to Bijapur procured the commodity from that kingdom in the Deccan in peninsular southern India and brought it to the Mughal court in Fatehpur which thereafter spread to the rest of the empire as interest grew around it. This envoy, an Iranian émigré and low-ranking courtier named Asad Beg Qazwīnī, left behind an account of his travels. Most works that narrate the incident refer to the oft-cited summary translation of select sections of Qazwīnī’s memoirs by Henry Elliot and John Dowson in their eight-volume The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. Recent studies have focused on the exotic quotient of the item procured from lands that lay beyond Mughal territorial frontiers and an object of wonder that excited Mughal imagination, leading to considerable debate in courtly society about its properties and effects of consumption.

However, despite sustained scholarly fascination with this event, what it can reveal about early modern diplomatic practices and material cultures has gone virtually unquestioned. Further, the episode offers crucial insights into the entangled networks of circulation and commercial exchange in the western Indian Ocean. In this blogpost, based on a critical analysis of Qazwīnī’s memoirs in the Persian manuscripts collections in the British Library, I relate how the Mughal envoy presented with great panache the tobacco and its accoutrements to Akbar during a courtly assembly held at the royal pavilion in the evening and delineate how courts emerged as spaces where both skills and objects were marketed.

Qazwīnī writes that although the tobacco was widespread in Bijapur, he had not come across the commodity in northern India (Hind), thereby instantly crediting himself for introducing something that Mughal court society was not familiar with and would thus be perceived as a novelty. Qazwīnī’s memoirs, written some years after his diplomatic stint, reads like a manual for aspirant envoys in many parts and here Qazwīnī implies that identifying, locating, and procuring rarities during travels to distant lands on diplomatic deputation were critical to an envoy’s profile.

Qazwīnī then goes on to give an intricate description of the chillum – the apparatus used to smoke the tobacco – which was produced in Mangalwedha (Solapur district, present-day Maharashtra), a frontier outpost of Bijapur where he had halted on his way to the kingdom. The golden chillum was studded with beautiful jewels and the roughly three-yards long reed (or smoking pipe, loosely) attached to it was sourced from Ujjain (present-day Madhya Pradesh), where too he halted both on his onwards and return journey to Bijapur. The highly matured reed was splattered with multiple hues and both its ends were enamelled (mīnā-kārī). Mīnā-kārī is an enamelling technique that originated in Iran during the Safavid-era for painting and colouring the surfaces of metals and ceramic tiles. Through networks of traders and artisans, this artform reached South Asia and flourished particularly in the courts of western India. Finally, the tip of the reed that was held by the hand in between the lips to smoke was fitted with delicate Yemeni cornelian, which would have arrived through the commercial traffic between the western coast of India and the Red Sea regions. Soon, the chillum would be replaced by the huqqa at the Mughal court – a device used for smoking tobacco filtered through water designed by emperor Akbar’s physician Ḥakīm ‘Alī Gilani (d. 1610) – that was richly decorated and gained rapid popularity across the Persianate world

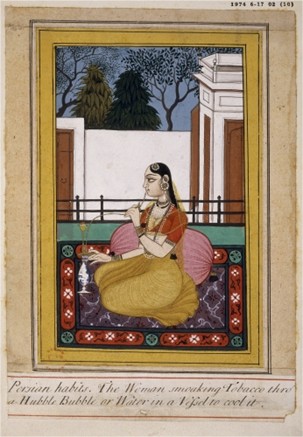

Figure 1: A woman smoking tobacco through a Hubble Bubble. Hyderabad, Deccan, India, late 17th century (British Museum)

Qazwīnī’s narrative underscores the varied materialities of the object comprising parts that were sourced from South Asia and the Indian Ocean world and assembled in Bijapur, thereby reinforcing the urban centre’s reputation as a thriving entrepot. The master craftsmanship of Bijapur artisans imparted an aesthetic dimension to the consumption of tobacco, apparent in the strikingly beautiful appearance of the chillum. A candle affixed on a gilded candlestand was used for igniting the tobacco. Qazwīnī was meticulous about presenting the rarities and took utmost care to arrange with precision the entire assortment upon a large silver plate before bringing it to the Mughal emperor. The tobacco and chillum were covered with a silver lid that was in turn wrapped in a delicate velvet jacket. The Mughal envoy portrays himself as a perfectionist with heightened aesthetic sensibilities who was well-aware of the currency that elegant presentation commanded in a Persianate courtly setting. In doing so, Qazwīnī powerfully drives home the point that, for an envoy returning to the court from a diplomatic mission, presentation of the exotica was as important as the act of acquiring it.

Figure 2: Chillum, c. 1880, Punjab, India (V&A)

When Qazwīnī brought the tray of tobacco and its accoutrements before Akbar’s attention, the emperor examined everything closely and gazed continuously at the chillum, indicating that he was impressed with its fine craftsmanship and appreciated Qazwīnī’s procurements. The text now adopts a dialogic form as Akbar asked Qazwīnī “what is this and how did you acquire it?” Even before Qazwīnī could respond, the emperor’s foster brother and prominent statesman, Mirzā ʿAzīz Koka, told him that “this is called tobacco, and it was widely prevalent in Mecca and Medina.” Mirzā ʿAzīz Koka had spent a year in the Hijaz (1593–4) when he had abandoned his governorship of Gujarat as an act of dissent against Akbar and had probably come across tobacco during his sojourn there. While Qazwīnī himself asserts (later in the episode) that the Portuguese popularized the circulation and consumption of tobacco, the possibility that the trans-Atlantic commodity may have been brought to the Deccan by indigenous merchants cannot be ruled out as the peninsular region enjoyed brisk trading relations with the Gulf of Aden for centuries. Tobacco thus seems to have been in steady circulation across the rims of the Indian Ocean from western Asia to the Deccan, but Mughal north India was left out of its ambit.

Another associated object that Qazwīnī presented before the courtly audience was a snuffbox of fine craftsmanship used for keeping pān (betel leaf) that the sultan Ibrāhīm ‘Ādil Shāh II (r. 1580–1627) had given him during his stay in Bijapur. The Mughal envoy filled it with fine quality tobacco and stated that when one betel leaf was ignited, the rest of the leaves also started burning. Qazwīnī thus draws our attention to a distinctive style of consumption that seems to have been in vogue in Bijapur. This method of rolling tobacco inside (or spreading them over) betel leaves and kindling them together appears to have been entirely different from puffing the substance using the chillum. Further, the smoke emanating from the concoction seems to have been induced with the flavor of pān as the two substances burnt simultaneously and could have possibly produced an impact on the senses different from smoking tobacco through a pipe fitted with a nozzle at its end. Qazwīnī impresses the Mughal emperor and his courtly circle with his knowledge of various methods of consuming tobacco that he had learnt, and the materiality of the processes as these involved using different objects and their respective functions.

Figure 3: Mughal boxes used to store areca nut, lime paste, and spices that are wrapped in betel vine leaf to make betel quid, commonly known as pān. Collections from northern India, 1600s (British Museum)

The highlight of the episode perhaps lies in the global convergences that both exotica represent. Tobacco, a trans-Atlantic commodity, travelled through Portuguese trading routes to the shores of the Indian Ocean, and was widely available both in the Hijaz and in Bijapur. It was consumed by the Bijapur courtly elite using a smoking apparatus (chillum) comprised of several parts sourced from different regions of Asia. The Deccan was a strategic node in the Indian Ocean trading networks owing to which it enjoyed access to a range of goods that were still beyond the reach of the Mughals. Tobacco reached Mughal north India much later through the hands of an envoy to the Deccan who presented it as a prized acquisition. Through his captivating storytelling abilities, Qazwīnī impresses upon his readers that rarities and practical knowledge acquired during travel and through diplomatic encounters were valuable resources to assert one’s finesse as an envoy. He lays tremendous emphasis on presentation that would complement the acquisition and do justice to the effort, thereby dropping a handy lesson in courtly comportment. By skilfully articulating the multiple materialities of the objects used for consuming tobacco, Qazwīnī reiterated how, in the early modern world, diplomacy was a conduit for cultural exchange and for the transmission of diverse knowledge systems rather than merely an avenue for conducting political relations between states.